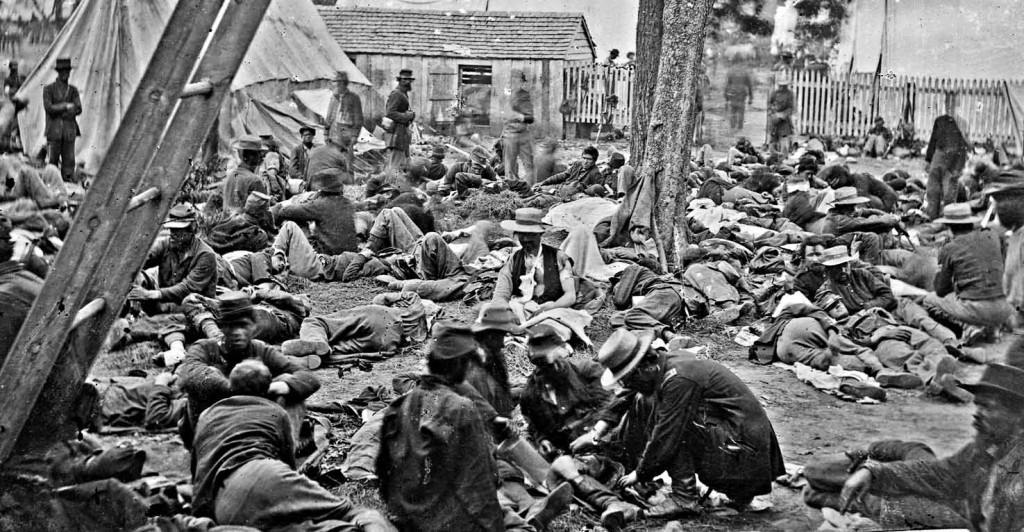

The American Civil War, which claimed the lives of more Americans than all other wars combined, ended 150 years ago today. As Senator Tom Cotton and other politicians breezily recommend bombing Iran, I recommend reading Walt Whitman’s “The Wound-Binder.”

Whitman begins his poem by imagining himself recounting his Civil War experiences to children in some distant future. Though they will want to hear about “hard-fought engagements or sieges tremendous,” he will instead tell them about war’s victims.

The poem in this way reminds me of Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est,” the phrase coming from Horace’s “Sweet and fitting it is to die for one’s country.” Like Whitman, Owen graphically describes the wounded—in this case the victim of a gas attack—in order to open the eyes of children “ardent for some desperate glory.” It’s clear to me that Owen knew Whitman’s poem:

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

In Whitman’s case, the qualifiers come in his parenthetical comments. He admits that he himself once had war fever before resigning himself “to sit by the wounded and soothe them, or silently watch the dead.” Rather than applauding only his own side, he sees all the wounded soldiers as worthy of respect:

An old man bending I come among new faces,

Years looking backward resuming in answer to children,

Come tell us old man, as from young men and maidens that love me,

(Arous’d and angry, I’d thought to beat the alarum, and urge relentless war,

But soon my fingers fail’d me, my face droop’d and I resign’d myself,

To sit by the wounded and soothe them, or silently watch the dead;)

Years hence of these scenes, of these furious passions, these chances,

Of unsurpass’d heroes, (was one side so brave? the other was equally brave;)

Now be witness again, paint the mightiest armies of earth,

Of those armies so rapid so wondrous what saw you to tell us?

What stays with you latest and deepest? of curious panics,

Of hard-fought engagements or sieges tremendous what deepest remains?

Whitman begins Section 2 with a soldier’s adrenaline rush as he charges the enemy. It then moves, however, to war’s tragic aftermath, even as “the world of gain and appearance and mirth goes on.” Soldiers may initially feel exhilarated as they “enter the captur’d works,” but this moment fades quickly (like a swift running river) and one is left with the poet entering hospital doors bearing “the bandages, water, and sponge.” When one soldier turns his anguished eyes to Whitman, the poet says that he would die in his place if he could:

O maidens and young men I love and that love me,

What you ask of my days those the strangest and sudden your talking recalls,

Soldier alert I arrive after a long march cover’d with sweat and dust,

In the nick of time I come, plunge in the fight, loudly shout in the rush of successful charge,

Enter the captur’d works—yet lo, like a swift running river they fade,

Pass and are gone they fade—I dwell not on soldiers’ perils or soldiers’ joys,

(Both I remember well—many of the hardships, few the joys, yet I was content.)

But in silence, in dreams’ projections,

While the world of gain and appearance and mirth goes on,

So soon what is over forgotten, and waves wash the imprints off the sand,

With hinged knees returning I enter the doors, (while for you up there,

Whoever you are, follow without noise and be of strong heart.)

Bearing the bandages, water and sponge,

Straight and swift to my wounded I go,

Where they lie on the ground after the battle brought in,

Where their priceless blood reddens the grass, the ground,

Or to the rows of the hospital tent, or under the roof’d hospital,

To the long rows of cots up and down each side I return,

To each and all one after another I draw near, not one do I miss,

An attendant follows holding a tray, he carries a refuse pail,

Soon to be fill’d with clotted rags and blood, emptied, and fill’d again.

I onward go, I stop,

With hinged knees and steady hand to dress wounds,

I am firm with each, the pangs are sharp yet unavoidable,

One turns to me his appealing eyes—poor boy! I never knew you,

Yet I think I could not refuse this moment to die for you, if that would save you.

Section 3 is filled with descriptions of crushed heads, amputated hands, and gangrenous wounds. “O beautiful death! In mercy come quickly,” Whitman says at one point. This section especially should be required reading for all war hawks:

On, on I go, (open doors of time! open hospital doors!)

The crush’d head I dress, (poor crazed hand tear not the bandage away,)

The neck of the cavalry-man with the bullet through and through I examine,

Hard the breathing rattles, quite glazed already the eye, yet life struggles hard,

(Come sweet death! be persuaded O beautiful death!

In mercy come quickly.)

From the stump of the arm, the amputated hand,

I undo the clotted lint, remove the slough, wash off the matter and blood,

Back on his pillow the soldier bends with curv’d neck and side falling head,

His eyes are closed, his face is pale, he dares not look on the bloody stump,

And has not yet look’d on it.

I dress a wound in the side, deep, deep,

But a day or two more, for see the frame all wasted and sinking,

And the yellow-blue countenance see.

I dress the perforated shoulder, the foot with the bullet-wound,

Cleanse the one with a gnawing and putrid gangrene, so sickening, so offensive,

While the attendant stands behind aside me holding the tray and pail.

I am faithful, I do not give out,

The fractur’d thigh, the knee, the wound in the abdomen,

These and more I dress with impassive hand, (yet deep in my breast a fire, a burning flame.)

In the final section, Whitman sees himself returning to these men in his dreams. Crucifixion imagery, found throughout the poem, appears in the final lines as Whitman describes crossed arms and a kiss. The poet is infused with a Christ-like sympathy and love for suffering humanity:

Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,

Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals,

The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand,

I sit by the restless all the dark night, some are so young,

Some suffer so much, I recall the experience sweet and sad,

(Many a soldier’s loving arms about this neck have cross’d and rested,

Many a soldier’s kiss dwells on these bearded lips.)

Gaze upon these sights, you masters of war, before you rush headlong into another one.