Spiritual Sunday

Please excuse my late post today. I am travelling home from my Carleton College 40th reunion and am only now getting to a place where I can post my essay.

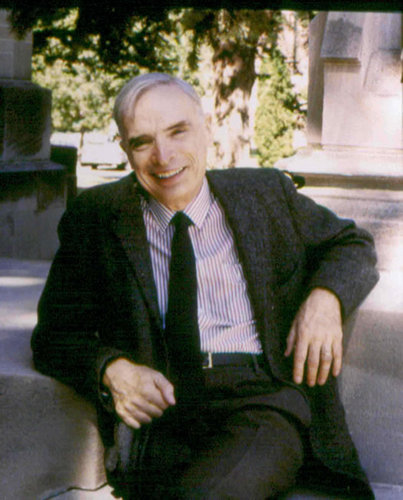

The flight home, however, has given me a chance to reflect upon a talk I heard by Carleton’s Templeton award-winning professor Ian Barbour on “Looking Back on Science and Religion from my 90th birthday.” Barbour cited a passage from Tennyson’s In Memoriam, which gives me an excuse to write about him here.

I had Barbour for a team-taught humanities class on the European Renaissance my first year, but I don’t remember him well because my breakout group was with a different professor. According to Barbour’s Wikipedia entry, PBS credited him with “literally creating the contemporary field of science and religion,” and the Templeton foundation, upon giving him its million dollar award, noted, “No contemporary has made a more original, deep and lasting contribution toward the needed integration of scientific and religious knowledge and values than Ian Barbour. With respect to the breadth of topics and fields brought into this integration, Barbour has no equal.” Barbour has a Ph.D in physics from the University of Chicago and a B.Div. from the Yale Divinity School. He has taught at Carleton all of his life.

[Allow me a quick digression regarding the man responsible for the Templeton award: I’d feel better about Templeton, who is from Franklin County, Tennessee, if he hadn’t desecrated the top of the Sewanee mountain with a godawful monument to himself.]

The Tennyson passage–“Nature red in tooth and claw”—is a reference to the survival of the fittest concept that early Darwinists believed governed evolution. Barbour cited it as he explored the meaning of the suffering in the world. He obviously appreciated the way that Tennyson struggles to reconcile his Christian faith with the untimely death of his best friend Hallam. Tennyson looked at the most advanced thinking of his age, including Darwininsm, in his search for meaning.

In this section of the poem, Tennyson is wrestling with the fact that many species (types) have become extinct. (Dinosaur bones were being discovered in rock quarries in the 19th century, thereby posing a deep challenge to traditional Christian notions of creation.) If humans could also become extinct—if spirit is no more that material breath and if those who have sung psalms to God and have seen God as Love will fare no better than any other biological organism—then life can appear as futile as it is frail. Or put another way, if Nature, red in tooth and claw, tears apart such trusting souls, then even the titanic struggles of dinosaurs seem mellow by comparison. The “She” that Tennyson addresses is the heavenly muse Urania who seems so focused on the spiritual realm and so uninterested in the material that she reproves Tennyson for looking to science to find spiritual answers:

“So careful of the type?” but no.

From scarped cliff and quarried stone

She cries, “A thousand types are gone:

I care for nothing, all shall go.

Thou makes thine appeal to me

I bring to life, I bring to death:

The sprit does but mean the breath:

I know no more.” And he, shall he,

Man, her last work, who seem’d so fair,

Such splendid purpose in his eyes,

Who roll’d the psalm to wintry skies,

Who built him fanes of fruitless prayer,

Who trusted God was love indeed

And love Creation’s final law—

Tho’ Nature, red in tooth and claw

With ravine, shriek’d against his creed—

Who loved, who suffer’d countless ills,

Who battled for the True, the Just,

Be blown about the desert dust,

Or seal’d within the iron hills?

No more? A monster then, a dream,

A discord. Dragons of the prime,

That tare each other in their slime,

Were mellow music match’d with him.

O life as futile, then, as frail!

O for thy voice to soothe and bless!

What hope of answer, or redress?

Behind the veil, behind the veil.

There are some scientists, of course, who don’t see the point of Tennyson’s and Barbour’s wrestling. Some are confident atheists like Richard Dawkins who, macho-like, act as though they don’t care if some day they will be “blown about the desert dust or seal’d within the iron hills.” Others just compartmentalize, putting the material and the spiritual in two different categories without seeking to join them. And of course we see many rightwing Christians who see the theory of evolution as (to quote the Georgia Congressman) “lies straight from the pit of hell.” But thinkers like Barbour and Tennyson, braving Urania’s disapproval, venture into this treacherous area.

Citing new discoveries in evolutionary biology, Barbour talked about biological instances where species ensure their future through cooperation rather than dominance. He talked of instances of empathy that have been discovered within primates. Making a link with religion, he talked of how, when dealing with evil, people sometimes turn towards power when a far stronger argument can be made for turning to love, even though the outcome seems less certain. He said that we need to regard whole systems at work in organisms, from the cultural to the psychological down to the molecular and that, rather than seeing ourselves in the grip of a determinism that shapes how we behave, we have choices we can make to resist evil. In a related way, he said he does not see God operating working on individual organisms but rather providing a spirituality that humans (and perhaps, in other ways, nature?) can draw on.

The question-answer session was fascinating. There were alumni there from a wide range of fields. An animal biologist from UCLA talked about new advances in primate behavior that support what Barbour was saying. Psychologist and novelist Patricia Coogan, who writes about native American spirituality, asked about polytheistic versions of God. (Barbour said that we need to listen to all religions for the various insights they can provide into the divine, and added that different religions have different strengths: Buddhism, he thought, has historically done better with environmental issues than Christianity but Christianity has done better with social justice issues.) A cultural anthropologist liked the intelligent way that Barbour talked about an empathy gene that scientists believe they have located. (Maybe we choose to activate the gene rather than being determined by it.) My wife asked about the apocalyptic visions we hear from certain rightwing evangelicals and Barbour reminded us that the Book of Revelations was written to keep hope alive at a dark time (following the destruction of the Temple by the Romans) and could not be read as a blueprint of the future.

It was a power-packed 75 minutes. For me, of course, the high point was the discovery that Tennyson is engaged in a search even more profound than I had realized with regard to science and faith. It will help me give urgency to In Memoriam when I teach it for the first time next semester.