My library book discussion group last night discussed The Bridge of San Luis Rey, a 1927 Thornton Wilder novel that has long been on my “read some day” list. It was the right book for the moment as I have been mourning two friends who died recently, faculty colleague Andy Kozak and fellow book group member Jane Aldridge.

The book originates from that most fundamental of questions, why death? Or more specifically, why does death strike randomly? Or does it?

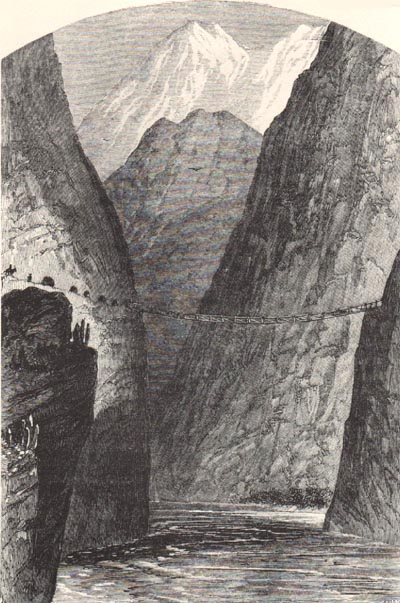

The last question is one that a witness to a tragic death is trying to answer. A Peruvian monk, one Brother Juniper, sees five people precipitated into the gulf when the Inca rope bridge they are crossing breaks. The novel is set in the 18th century so, in the spirit of the Enlightenment, he sets out to study the five people to see if he can figure out how God intervenes in the world. He fails and, to make matters worse, the Inquisition takes offense at his investigation and burns both him and his book at the stake.

Our group found ourselves discussing not only the book but Jane, who died suddenly while on a travel tour to Malta. As we shared what we knew, we realized that we were trying to make sense of what in the end makes no sense, which is Wilder’s point. Although all the bridge victims can be linked, the connections don’t add up to an explanation.

As we read what Brother Juniper has uncovered about their lives, however, we come to learn that each has a great soul, despite unpromising exteriors. We especially see this in a pathetic old marquesa who discovers an unexpected fount of selfless love and writes an extraordinary letter to her estranged daughter right before she dies. Wilder reminds me a bit of Isak Dinesen in the way he reveals inner luminescence.

We learn from the novel’s concluding section that Juniper fails to find connections because he looks only at those who have died. The real connections grow amongst the survivors. For instance, the Abbess, who feels like her work is for naught because of the deaths of the two orphans (Pepita and Esteban), finds new meaning when the daughter of a marquesa shares the letter with her:

The Consesa showed the Abbess Dona Maria’s last letter. Madre Maria dared not say aloud how great her astonishment was that such words (words that since then the whole world has murmured over with joy) could spring in the heart of Pepita’s mistress. “Now learn,” she commanded herself, “learn at last that anywhere you may expect grace.” And she was filled with happiness like a girl at this new proof that the traits she lived for were everywhere, that the world was ready.”

In the end, the Abbess, the daughter, and the mother of a boy who was killed nurture each other. Before the accident they had been facing estrangement of one sort or another, but now their lives have taken on new significance.

As the Abbess sees it, the bridge of death has become a bridge of love. It is a link between the land of the living and the land of the dead that sustains us when all appears meaningless:

“Even now,” she thought, “almost no one remembers Esteban and Pepita, but myself. Camila alone remembers her Uncle Pio and her son; this woman, her mother. But soon we shall die and all memory of those five will have left the earth, and we ourselves shall be loved for a while and forgotten. But the love will have been enough; all those impulses of love return to the love that made them. Even memory is not necessary for love. There is a land of the living and a land of the dead and the bridge is love, the only survival, the only meaning.”

Bridge of San Luis Rey was a good book for the Advent season. When our group exited from the library, we were greeted by the neighborhood Christmas and Hanukkah lights.