Last week I gave a list of my favorite children’s books when I was young. My father, who is a poet along with being a French professor, read us poetry as well as fiction (each night, one story or chapter and one poem for each of my three brothers and me), so I thought I’d pass along my favorite poems from that time.

Poetry encourages children to play with language, which they are in the process of learning, and with the world, which they are trying to figure out. (This world doesn’t always make a lot of sense.) Since play is work for children, the distinction between art and reality doesn’t seem to them to be as hard and fast as it does to adults. The following poems taught me vital lessons and offered me a fair amount of solace and support when I was a child.

Jack Sprat, the old woman who lived in a shoe, Jack and Jill, the old man clad in leather, Little Bo Peep, Little Miss Muffit, Humpty Dumpty, Mistress Mary quite contrary—these figures and many more were as present to me as my friends. In fact, the poems gave me a sense that I knew scores of people, each with his or her little drama presented in a short and compelling set of rhymes. A sorrow to me as I teach now is how few of my students know the Mother Goose rhymes.

Dr. Seuss

Many of the best Dr. Seuss books are in rhyme, including my first one, The Cat in the Hat. The mayhem caused by the cat (and by Thing 1 and Thing 2) was a guilty pleasure for me, given that I, as the oldest child, identified with the fish and was struck with fear at the prospect of the mother’s return. I still recall the fish’s panic as we see the mother approaching through the window and remember the deep relief when order is miraculously restored. I also remember my amazement at how, by just switching one letter, one could turn the word cat into hat into sat into mat. Language seemed to me magical.

A. A. Milne, When We Were Very Young and Now that I’m Six

I loved Milne’s poems as much as his Pooh tales. Many have a wonderful bounce to them, with their meter and rhyme making absurd stories sound plausible. Of course all sorts and conditions of famous physicians will come hurrying around at a run when Christopher Robin has wheezles and sneezles. Of course it makes sense that the king would only want a little bit of butter for his bread. Of course King John would want an India rubber ball for Christmas. All this makes sense to a child.

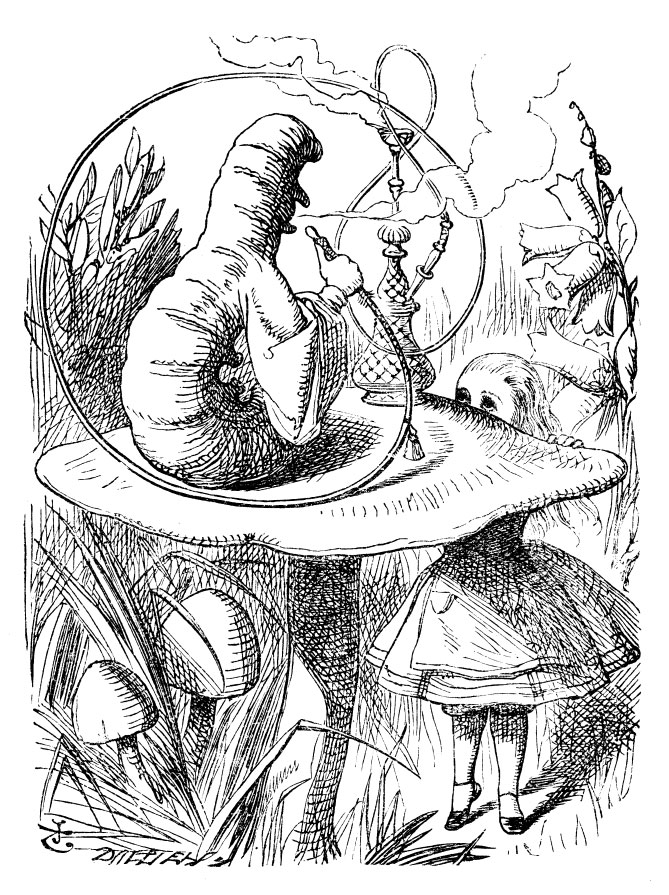

The Poetry of Lewis Carroll

I especially loved the poetry in the Alice books, where dry, didactic poems (“You are Old Father William,” “How Doth the Little Busy Bee”), designed for make children good, are inverted into glorious nonsense. The nonsense, in fact, is the weapon that Carroll gives children for fighting back against a Victorian morality that could become stultifying. Note how, when some cranky adult figure (the mouse, the caterpillar, the mock turtle), orders Alice to recite poetry, she very innocently twists it in knots. When, years later, I discovered the original targets of Carroll’s parodies in Martin Gardiner’s Annotated Alice, I was even more impressed.

Hilaire Belloc, Cautionary Tales for Children

In a darker strain than Carroll, Hllaire Belloc engages in black comedy in which disasters befall children who misbehave. Such as “Jim, who ran away from his nurse and was eaten by a lion” and “Matilda, who told lies, and was burned to death” (“And every time she shouted fire,/ They only answered, ‘Little liar.’”) Belloc may have been parodying the truly terrifying Der Struwwelpeter poems by Heinrich Hoffmann, German verse designed to terrify children into being good (especially the scissor man who visits children who suck their thumbs and cuts them off). Like Carroll, Belloc knew that children can feel oppressed by all the rules thrust at them, and his poems help children find a refuge.

The Poetry of Edward Lear

Edward Lear is a rival of Lewis Carroll for nonsense poetry, once again offering children a poetic counterweight to pragmatic bourgeois society. My favorite was “The Courtship of the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bo,” which was simultaneously ridiculous and sad. I also loved “The Jumblies” and “The Owl and the Pussycat.” When my wife was giving birth to Justin and needed to hear the sound of my voice for long stretches of time, I recited “The Yonghy-Bonghy-Bo” over and over again and it provided a kind of incantatory comfort.

Alfred E. Noyes, “The Highwayman” and “Song of Sherwood”

Perhaps no poem is more romantic, especially to middle schoolers, than “The Highwayman.” Maybe it’s the metaphor of the “moon as a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas” that pulls one in. “Song of Sherwood” is enchanting in another way, calling upon the world of the imagination to awake: “Sherwood in the red dawn, is Robin Hood asleep?”

James Whitcomb Riley, “Little Orphant Annie” and “The Raggedy Man”

Some poems cry out to be read out loud and I had a father who was up to the challenge Riley, writing in dialect, gave us working class characters who knew how to talk to children and with whom we could imagine having a special bond. In other words, a few marginal adults out there understand how the world as we children understood it. Such as Little Orphant Annie, who tells her charges that “the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you Ef you Don’t Watch Out!”

Rudyard Kipling, “Gunga Din”

I can’t leave “Gunga Din” off this list, identifying as I did with the heroic water boy who gains the grudging respect of the bossy (and racist) soldiers. It’s good for a child’s self esteem to be assured that, “Though I’ve belted you and flayed you, by the livin’ Gawd that made you,you’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!” Some of Kipling’s Just So Stories, incidentally, are just as rhythmic and wonderful to read aloud as his poetry, such as “The Song of Old Man Kangaroo.”

Louis Untemeyer, The Golden Treasury of Poetry

Untermeyer’s wonderful anthology of children’s poetry was filled with, among other things, long melodramatic Victorian poems like Longfellow’s “The Wreck of the Hesperus” and Rose Hartwick Thorpe’s “Curfew Must Not Ring Tonight.” They are not what we think of as great poetry but they were on my child’s wavelength. The fact that, at this age, I also liked fizzies and other cloying sweets could be seen as a sign that we need to outgrow some poems. On the other hand, little that I drink today has the same punch as the fizzies I remember.

Oliver Goldsmith, “Elegy on the Death of a Mad Dog”

Here is another poem that appeals to a child’s sense that the world has its priorities upside down. Who dies when the self-righteous man is bitten by a mad dog? Not the man. Life is so unfair!

Walter De La Mare, “The Listeners”

And finally, the great Gothic poem that affirmed for me that the world was filled with delicious mystery. The integrous traveler has kept his word in the face of the silence of the universe. That’s all we need to know.

2 Trackbacks

[…] I’ve mentioned in earlier posts, my father proceeded to read all his favorite books to me. Interestingly, I think we avoided the last chapter of The House at Pooh Corner, which hints at a […]

[…] intimations of mental mortality are, of course, partly Robin’s fault. Why? It was after reading one of his blog entries that I decided to guarantee my daughter a poem a night. Robin wrote something simple like, “My […]