Note: Comments can be sent to [email protected]. Also, you may write me there if you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Tuesday

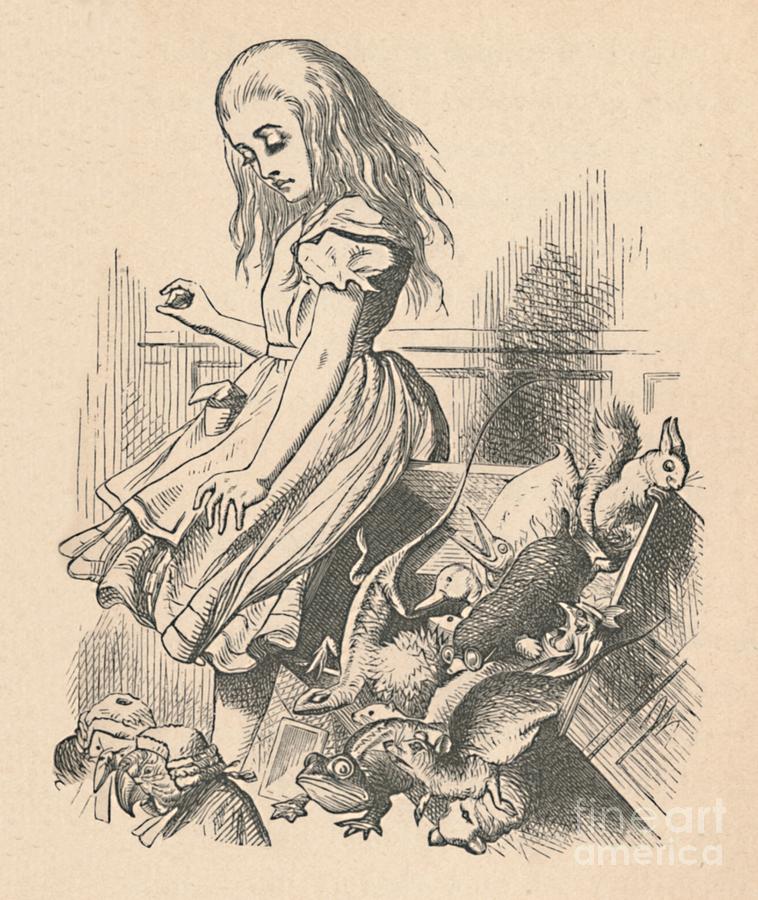

Kudos to Sunday’s Washington Post for using Lewis Carroll’s Alice books to explain the Trump trials. In the article, reporters Devlin Barrett and Perry Stein invite us to follow them down the legalistic rabbit hole.

The article is entitled “The Trump Trials: Aileen in Wonderland,” Aileen being Judge Aileen Cannon, who is presiding over the stolen documents case in Palm Beach, FL. Cannon’s orders are confusing judicial experts. One former judge observed, “In my 30 years as a trial judge, I have never seen an order like this.” Another, citing the White Queen in Through the Looking Glass, said Cannon appeared to be “believing impossible things.” At one point the queen has the following interchange with Alice:

“Now I’ll give you something to believe. I’m just one hundred and one, five months and a day.”

“I can’t believe that!” said Alice.

“Can’t you?” the Queen said in a pitying tone. “Try again: draw a long breath, and shut your eyes.”

Alice laughed. “There’s no use trying,” she said: “one can’t believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.

Cannon’s belief in impossible things, according to another Post article, shows up in a ruling that suggests

an openness to some of the defense’s claims that the Presidential Records Act allows Trump or other presidents to declare highly classified documents to be their own personal property. National security law experts say that is not what the law says, or how it has been interpreted over decades by the courts, particularly given the other laws that govern national security secrets.

Cannon apparently also issued

an unusual order late Monday regarding jury instructions at the end of the trial — even though she has not yet ruled on when the trial will be held, or a host of other issues.

To which the Post reporters commented that the orders have become “curiouser and curiouser”–which is Alice’s response to her rapid growth after she eats a piece of cake:

“Curiouser and curiouser!” cried Alice (she was so much surprised, that for the moment she quite forgot how to speak good English); “now I’m opening out like the largest telescope that ever was! Good-bye, feet!” (for when she looked down at her feet, they seemed to be almost out of sight, they were getting so far off).

Cannon too appears to be losing sight of something, namely the actual law that Trump is accused of having broken. The reporters note that, by “ordering lawyers in the case to submit proposed jury instructions under two different legal theories, Cannon

is setting the table for a trial that would look like a Mad Hatter tea party — a gathering run by a broken clock, in which everyone inexplicably switches seats. And at the rate she’s going, that party may not happen this year.

The Post article applies another Wonderland episode to the case that Manhattan prosecutor Melvin Bragg is bringing against Trump for hush money payments and violation of election laws. Trump’s lawyers are arguing that Bragg has mishandled evidence “recently turned over by their federal counterparts a few blocks away,” claiming that this “should lead to dismissal of the charges and sanctions for the prosecutors.” In response,

Bragg called Trump’s accusations against him a “grab bag” of nonsensical legal arguments, or, as they say in Wonderland: “Let us both go to law: I will prosecute you — Come, I’ll take no denial; We must have a trial.”

The reference here is to the poem recited by the mouse to Alice and the other creatures that have escaped from the pool of tears in Wonderland. The cat in the poem, however, resembles Vladimir Putin, rather than the American judicial system:

Fury said to a

mouse, That he

met in the

house,

‘Let us

both go to

law: I will

prosecute

you.—Come,

I’ll take no

denial; We

must have a

trial: For

really this

morning I’ve

nothing

to do.’

Said the

mouse to the

cur, ‘Such

a trial,

dear sir,

With

no jury

or judge,

would be

wasting

our

breath.’

‘I’ll be

judge, I’ll

be jury,’

Said

cunning

old Fury:

‘I’ll

try the

whole

cause,

and

condemn

you

to

death.’

The final Alice allusion occurs in relation to the Georgia trial, where Trump and his campaign are accused of attempting to overturn the 2020 Georgia election results. One of the issues is whether Trump should be allowed to remain free while his trial is underway. The Post reporters, who believe that Trump does not in fact represent a flight risk, observe,

In Wonderland, the queen liked to shout “off with her head,” and insist the sentence should come before the verdict. “Stuff and nonsense,” Alice said, “The idea of having the sentence first.” The U.S. legal system largely agrees with Alice, and says the only reasons to put someone in jail before a trial is if they pose a risk of flight, or a danger to the community.

I don’t find this a very effective use of Alice. A better example would be those Trump supporters who have called for Hillary Clinton to be locked up or Joe Biden to be impeached for crimes to be determined later.

If Trump manages to be reelected, Queen of Hearts justice—or Fury justice—will become the order of the day. Pray that the rule of law successfully wields the vorpal blade against jabberwockian anarchy.