Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at [email protected]. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Tuesday

Since I’m currently in the process of setting up a C.S. Lewis symposium for our church, I’ve been rereading the Narnia series. Most of the books, especially The Silver Chair, hold up very well, but I’ve just been reminded how unpleasant The Last Battle is. It’s everyone’s least favorite book and with good reason.

Because Narnia’s inhabitants have been duped by a false Aslan, most have become either cynical nonbelievers or lost souls, which means that King Tirian and his unicorn companion Jewel can’t rally them to fight for their freedom. As a result, everyone dies, with C.S. Lewis reenacting the Biblical Book of Revelations to bring his series to an apocalyptic conclusion.

To be sure, it’s not totally depressing as everyone we like gets to go to Narnia Heaven. Still, we have to wade through a lot of yuk to get there. One of the yukkiest scenes reminds me of the bothsiderism that is characterizing much of the 2024 election coverage.

Bothsiderism in our case is the press giving the fascist who is running for president the same treatment as his opponent. Whatever Joe Biden’s flaws, he is not promising to weaponize the Department of Justice against his political enemies nor promising to be “dictator on day one” nor giving state secrets to the Russians. Humorist David Sedaris memorably captured the situation when he wrote (this in the final weeks of the 2008 election)

I think of being on an airplane. The flight attendant comes down the aisle with her food cart and, eventually, parks it beside my seat. “Can I interest you in the chicken?” she asks. “Or would you prefer the platter of shit with bits of broken glass in it?”

To be undecided in this election is to pause for a moment and then ask how the chicken is cooked.

I’ll grant that it’s debatable that Sedaris’s illustration applies to Barack Obama running against John McCain. (Then again, Sarah Palin helped tilt it into shit-with-glass territory.) But it’s definitely the situation now, just as it was when Social Democratic and Centre candidates were running against Adolph Hitler in the 1933 German federal election.

Those media outlets treating 2024 as just another election are like the dwarfs in Last Battle. The Calormenes have used a fabricated god to gain control over Narnia, including to persuade the dwarfs to slave for them in the mines. When Tirian frees the dwarfs and then tries to rally them to his cause, however, they aren’t having any of it. To be sure, at first things appear hopeful as they join with him, helping beat back a Calormene assault. But the aid they provide is illusory:

“Had enough, Darkies?” they yelled [at the Calormenes]. “Don’t you like it? Why doesn’t your great Tarkaan go and fight himself instead of sending you to be killed? Poor Darkies!”

“Dwarfs,” cried Tirian. “Come here and use your swords, not your tongues. There is still time. Dwarfs of Narnia! You can fight well, I know. Come back to your allegiance.”

“Yah!” sneered the Dwarfs. “Not likely. You’re just as big humbugs as the other lot. We don’t want any Kings. The Dwarfs are for the Dwarfs. Boo!”

This is bothsiderism at its clearest. Rather than seeing Trump as a clear and present danger to a free press, too many journalists see it as their job to treat both sides as equal humbugs. Hillary Clinton gets the same treatment for a minor e-mail violation that Trump does for a clear record of rape and fraud while Biden is hammered for his age.

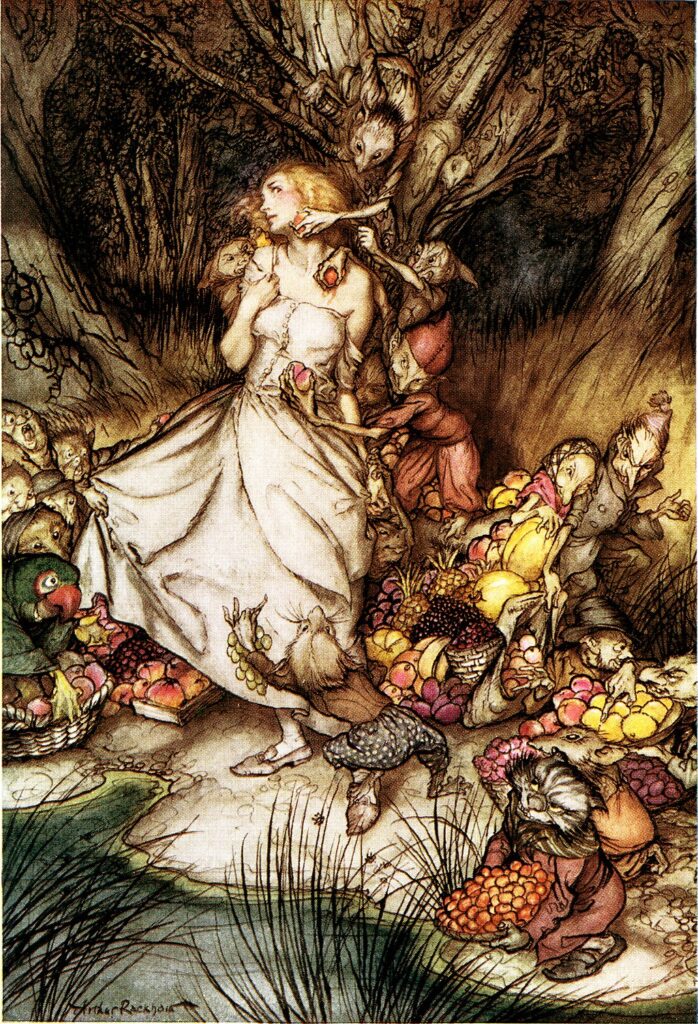

In Last Battle, the dwarfs treating each side equally leads to the saddest scene in the entire book. Tirian has managed to rally some of the talking animals to his side and has sent off the mice, moles and squirrels to gnaw the ropes of talking horses that have been imprisoned by the Calormenes. Then this happens:

With a thunder of hoofs, with tossing heads, widened nostrils, and waving manes, over a score of Talking Horses of Narnia came charging up the hills. The gnawers and nibblers had done their work.

Poggin the Dwarf and the children opened their mouths to cheer but that cheer never came. Suddenly the air was full of the sound of twanging bowstrings and hissing arrows. It was the Dwarfs who were shooting and—for a moment Jill could hardly believe her eyes—they were shooting the Horses. Dwarfs are deadly archers. Horse after horse rolled over. Not one of those noble Beasts ever reached the King.

When Eustace expresses his horror, the dwarfs respond like newspapers shrugging off liberal critics:

[T]he Dwarfs jeered back at Eustace. “That was a surprise for you, little boy, eh? Thought we were on your side, did you? No fear. We don’t want any Talking Horses. We don’t want you to win any more than the other gang. You can’t take us in. The Dwarfs are for the Dwarfs.”

Now, I’m not saying that mainstream media should turn into a leftist version of Fox News. The problem is that, by reporting “Democrats say-Republicans say” in an even-handed manner, the press actually helps the side that traffics most in lying and disinformation. The falsehoods become part of the discourse and are thereby normalized. As NYU journalism professor Jay Rosen points out, while “some lies and acts of disinformation are too important to be ignored, … repeating them in news accounts only helps them spread.”

So what to do? He, along with strategic language expert George Lakoff, argues for a truth sandwich. Rosen describes it as follows:

First state what is true. Then introduce the truthless or misleading statement. Then repeat what is true, so that the falsehood is neither the first impression nor the takeaway.

Too many in the media are seeing it more as their job to balance their coverage than to “state what is true.” By doing so, they could suffer the same fate as the dwarfs, who end up as dead as the Narnians. Or in Lewis’s metaphorical version of death, find themselves thrown into a dark stable.

In other words, Biden is fighting to save a democracy that ensures press freedom no less than free and fair elections.