Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at [email protected]. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well

Friday

As today is Algernon Charles Swinburne’s birthday, I share his best-known poem, which also might be considered an anti-spring poem. And that’s okay. Just because buds are bustin’ out all over doesn’t mean that we have to feel energized. In fact, T.S. Eliot considered April to be the cruelest month. After all, it breeds

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

So okay, I grant that Eliot’s preferred state here is one of emotional numbness—”Winter kept us warm, covering earth in forgetful snow.” Still there are those times when “the world is too much with us” (to quote Wordsworth) and we just want to rest. I think of the final lines of Tennyson’s “Lotus Eaters”:

Surely, surely, slumber is more sweet than toil, the shore

Than labour in the deep mid-ocean, wind and wave and oar;

O, rest ye, brother mariners, we will not wander more.

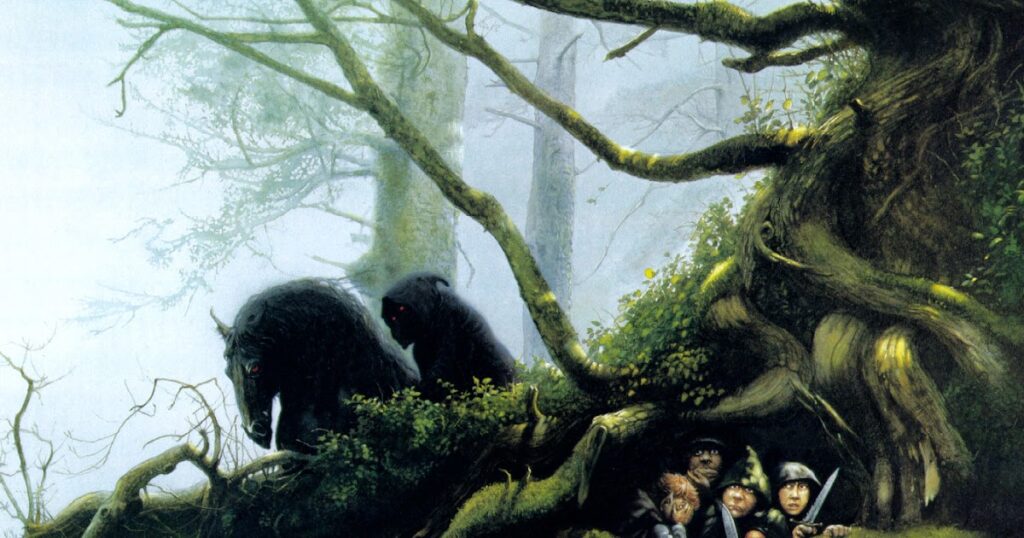

Swinburne appears to be coming from a similar place in “The Garden of Proserpine.” Proserpine was the daughter of Ceres, goddess of the harvest, and was carried off to the kingdom of the dead by Pluto. When her mourning mother stopped growing crops, the gods pressured Pluto to release her. But because Proserpine had eaten six pomegranate seeds in the underworld, she had to stay there every six months of the year.

Swinburne’s speaker, on the other hand, appears to want to be there year-round. He is “tired of tears and laughter” and pretty much everything else associated with living. “Even the weariest river,” he writes, “winds somewhere safe to sea.” Here’s the poem:

The Garden of Proserpine

By Algernon Swinburne

Here, where the world is quiet;

Here, where all trouble seems

Dead winds’ and spent waves’ riot

In doubtful dreams of dreams;

I watch the green field growing

For reaping folk and sowing,

For harvest-time and mowing,

A sleepy world of streams.

I am tired of tears and laughter,

And men that laugh and weep;

Of what may come hereafter

For men that sow to reap:

I am weary of days and hours,

Blown buds of barren flowers,

Desires and dreams and powers

And everything but sleep.

Here life has death for neighbour,

And far from eye or ear

Wan waves and wet winds labour,

Weak ships and spirits steer;

They drive adrift, and whither

They wot not who make thither;

But no such winds blow hither,

And no such things grow here.

No growth of moor or coppice,

No heather-flower or vine,

But bloomless buds of poppies,

Green grapes of Proserpine,

Pale beds of blowing rushes

Where no leaf blooms or blushes

Save this whereout she crushes

For dead men deadly wine.

Pale, without name or number,

In fruitless fields of corn,

They bow themselves and slumber

All night till light is born;

And like a soul belated,

In hell and heaven unmated,

By cloud and mist abated

Comes out of darkness morn.

Though one were strong as seven,

He too with death shall dwell,

Nor wake with wings in heaven,

Nor weep for pains in hell;

Though one were fair as roses,

His beauty clouds and closes;

And well though love reposes,

In the end it is not well.

Pale, beyond porch and portal,

Crowned with calm leaves, she stands

Who gathers all things mortal

With cold immortal hands;

Her languid lips are sweeter

Than love’s who fears to greet her

To men that mix and meet her

From many times and lands.

She waits for each and other,

She waits for all men born;

Forgets the earth her mother,

The life of fruits and corn;

And spring and seed and swallow

Take wing for her and follow

Where summer song rings hollow

And flowers are put to scorn.

There go the loves that wither,

The old loves with wearier wings;

And all dead years draw thither,

And all disastrous things;

Dead dreams of days forsaken,

Blind buds that snows have shaken,

Wild leaves that winds have taken,

Red strays of ruined springs.

We are not sure of sorrow,

And joy was never sure;

To-day will die to-morrow;

Time stoops to no man’s lure;

And love, grown faint and fretful,

With lips but half regretful

Sighs, and with eyes forgetful

Weeps that no loves endure.

From too much love of living,

From hope and fear set free,

We thank with brief thanksgiving

Whatever gods may be

That no life lives for ever;

That dead men rise up never;

That even the weariest river

Winds somewhere safe to sea.

Then star nor sun shall waken,

Nor any change of light:

Nor sound of waters shaken,

Nor any sound or sight:

Nor wintry leaves nor vernal,

Nor days nor things diurnal;

Only the sleep eternal

In an eternal night.

In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Sigmund Freud theorizes that there is a desire within cells to return to their previous inanimate state, a drive he called the death wish or Thanatos. This exists in tension with Eros, the life drive, with sometimes one predominant, sometimes the other. Swinburne’s poem can be seen as an homage to Thanatos.

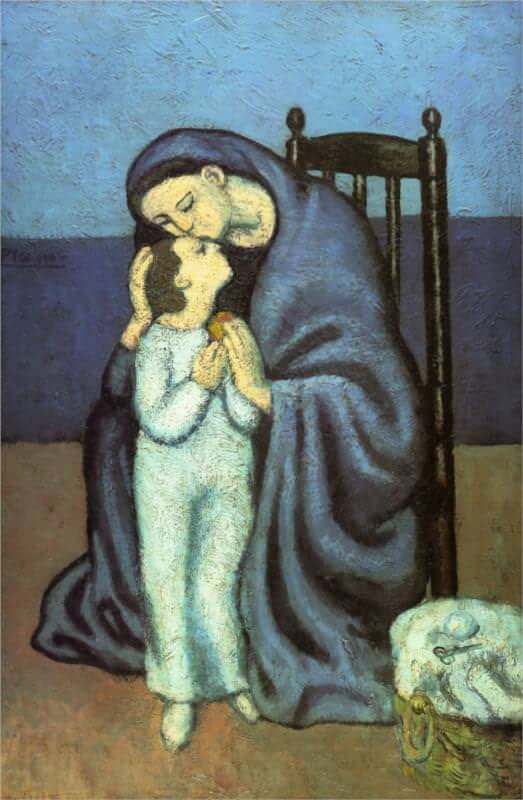

I remember, in college, being drawn to “Garden of Proserpine” when I was at the end of an arduous semester and was feeling wrung out. Given all the pressure that I placed on myself, an inanimate state seemed pretty good to me. One of my favorite paintings has always been Daniel Gabriel Rossetti’s painting Proserpine, which was inspired by the poem and which hangs in our living room. In it one sees Proserpine almost defiantly biting into a pomegranate—like Eve biting into the apple—as though, like Swinburne’s speaker, she wants to remain.

I’m not recommending world-weary poems for all occasions. Sometimes, however, there’s consolation in finding a lyric that makes your exhaustion feel poetic.