One thing I appreciate about the New York Times is that many of its columnists routinely mention literature. Maureen Dowd probably does so the most (note this passing reference to T. S. Eliot’s Wasteland), and I once wrote a column on Roger Cohen’s use of The Great Gatsby in a piece on President Obama. (Cohen wrote that, while he appreciated Obama’s grasp of reality, he feared that America is a land so filled with Gatsby-like dreamers that Obama would have a hard time connecting.)

I also had fun extending the ideas suggested by a Paul Krugman article where he imagined Tiny Tim receiving health care in America, first with and then without Obamacare. (Tiny Tim, of course, has a preexisting condition and Scrooge is not the kind of employer to offer health benefits.) Then, this past week, Krugman applied Jonathan Swift’s “Modest Proposal” to the current meltdown of the Irish economy, caused by rapacious banks. Krugman casts the bankers for the role that, in Swift’s famous essay advocating eating the babies of the poor, is played by landlords—“who, as they have already devoured most of the parents, seem to have the best title to the children.”

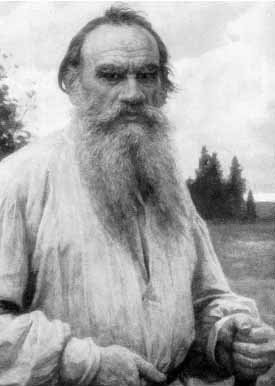

But today I want to steer your attention towards an interesting column by David Brooks on Leo Tolstoy. Brooks, who periodically reflects on the difference between the poetry of political idealism and the prose of governing (and of running corporations), takes up a related dualism: between the novelist and the prophet/activist.

I have periodically written on this website that literature works differently than politics because one is geared towards exploring ambiguity, nuance, and complication while the other is focused on making things happen in the world. While the best politicians and leaders appreciate the complex insights that literature provides, in the end they must move past reflection to action. Brooks sees Tolstoy torn between these two poles. On the one hand, he had dreams of saving the world. But

when he sat down to write his great novels, his dreams of saving mankind were bleached out by the vividness of the reality he saw around him. Readers often comment that the worlds created in those books are more vivid than the real world around them. With Olympian detachment and piercing directness, Tolstoy could describe a particular tablecloth, a particular moment in a particular battle, and the particular feeling in a girl’s heart before a ball.

Brooks goes on to quote Isaiah Berlin, who

famously argued that Tolstoy was a writer in search of Big Truths, but his ability to see reality in all its particulars destroyed the very theories he hoped to build. By entering directly into life in all its contradictions, he destroyed his own peace of mind.

As Tolstoy himself wrote, “The aim of an artist is not to solve a problem irrefutably, but to make people love life in all its countless, inexhaustible manifestations.”

Brooks argues that the two phases of Tolstoy’s life, the novelist and the crusader, each “called forth its own way of seeing.” Tolstoy could only see the world clearly as an observer. As an activist, on the other hand, he was blinded. “He preached universal love,” Brooks writes, “but seemed oblivious to the violence he was doing to his family.”

To his credit, Brooks concludes simply by presenting the two conflicting phases, not by attempting to reconcile them or by choosing one over the other. As he sees it, the contradiction is one of life’s mysteries:

In middle age, it was as a novelist that Tolstoy achieved his most lasting influence. After all, description is prescription. If you can get people to see the world as you do, you have unwittingly framed every subsequent choice.

But public spirited, he also wanted to heal the world directly. Tolstoy devoted himself to activism and spiritual improvement — and paid the mental price. After all, most historical leaders write pallid memoirs not because they are hiding the truth but because they’ve been engaged in an activity that makes it impossible for them to see it clearly. Activism is admirable, necessary and self-undermining — the more passionate, the more self-blinding.

One Trackback

[…] the events of the day. I reported on one such New York Times outbreak a couple of years ago (go here). There’s been another outbreak of literature sightings in the last couple of […]