As I am out of town this week, colleagues of mine have been gracious enough to loan me articles for my website. The following was written by Ben Click, our department chair and a Mark Twain scholar. In addition to talking about Twain’s remarkable stage presence, the article announces a Twain colloquium that Ben is organizing for April 24. Calling himself a shameless promoter in the proud tradition of Twain, Ben tells me that tickets are still available for a before-the event fundraising dinner. The event itself is free. For information, click here.

The article appeared in the February 2010 issue of The River Gazette.

By Ben Click

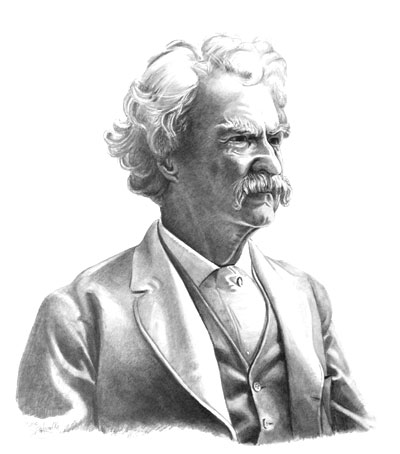

We all know of Twain’s reputation as a great American writer, but he was equally known in his lifetime as a mesmerizing public speaker, delivering nearly a 1000 lectures and speeches. He enthralled whether delivering a formal talk or offering a seemingly impromptu remark to a reporter’s question.

But what was it like to witness Mark Twain speaking? Alfred Bigelow Paine, Twain’s first biographer and literary executor, described the experience this way: “Not to have heard Mark Twain is to have missed much of the value of his utterance. He had immeasurable magnetism and charm . . . no one could resist him.”

This article not only discusses Twain as a public speaker, but also offers distilled, shameless promotion for this year’s Annual Twain Lecture. Twain would appreciate that—he being one of the great self-promoters in American history.

In his first major public speaking engagement in 1866 he chose to introduce himself: “The next lecture in this course will be delivered this evening by Samuel L. Clemens, a gentleman whose high character and unimpeachable integrity are only equaled by his comliness of person and grace of manner. And I am that man!” A rather bold play for humor from a man suffering severe stage fright and “quaking in every limb with a terror that seemed like to take [his] life away.”

His worries were compounded because he thought he would be speaking to an empty house. Again, he relied on his gift for exaggeration to promote the event. The handbill for the lecture advertised in bold and capitalized letters a “A Splendid Orchestra,” “A Den of Ferocious Wild Beasts,” “Magnificent Fireworks,” and “A Grand Torchlight Procession.” Beneath each attraction were lower-cased disclaimers, respectively: “Is in town, but has not been engaged,” “Will be on exhibition in the next block,” “were in contemplation for this occasion, but the idea has been abandoned,” and “May be expected; in fact, the public are privileged to expect whatever they please.” The “dress circle” paid a $1.00 for admission, the “family circle” $ 0.50. The doors opened at 7 and the “trouble [began] at 8.”

This initial bout with stage fright passed with the first laugh as did his worry about attendance at his talks. For the rest of his life, he spoke publicly in all kinds of forums: lecture halls, formal banquets, after-dinner speeches, fund-raising campaigns, and interviews. His topics ranged from reporting on his trip to the Sandwich Islands (now known as Hawaii) to introducing Winston Churchill to his first American audience. His formal talks seemed more like conversational monologues developed on the spot, but in fact he was a tireless preparer of his lectures who spent days memorizing them. He spoke in a lazy drawl, his facial expression almost severe with his piercing eyes trained on his audience when delivering an especially sardonic line. He employed few gestures but would lean causally on the podium if one were available. As Twain scholar Paul Fatout states: “His presence at any occasion . . . assured a large audience as certainly as Caruso’s name in the cast of an opera packed the house at the Metropolitan.”

St. Mary’s College hopes to pack the house (well, it’s actually the gym) come April 24, 2010 for the Annual Twain Lecture as we offer a “kick-off” event to celebrate the Twain Centennial. (He actually died on April 21, 1910, but the inconvenience of that being a Wednesday night caused us to change the date.) We considered the ferocious wild beasts, magnificent fireworks, and torchlight procession, but fire codes prevented it. Instead, we give you a “once-in-a-lifetime” event (your lifetime, not Twain’s): Twain’s Relevance Today: Race, Religion, Politics, and ‘the Damned Human Race

Witness a popular quiz show host moderate a panel consisting of a media gadfly, a Twain scholar, and a political analyst as they respond to questions about Twain and the topics above.

Our cast of characters:

The Witty Toastmaster: Peter Sagal, host of NPR’s Wait, Wait . . . Don’t Tell Me! will serve in this role—a role usually reserved for an ass according to Twain. He viewed most who filled the role as unimaginative and too stodgy to arouse enthusiasm. But Twain would approve of Sagal who describes his show as “NPR without the dignity. We say things on the radio that most people just shout at the radio.” That’s hardly unimaginative and stodgy, and he’s anything but an ass. For Twain,“Irreverence is the champion of liberty and its only sure defense.”

The Media Gadfly: Mo Rocca, contributor to the Tonight Show and CBS’s Sunday Morning, former correspondent to The Daily Show with John Steward, and regular on “Wait, Wait . . .” plays a role that Twain himself relished. Like Twain, Rocca is famed for his “fake news” reports as a means of chiding the world of news media. Similarly, Twain critiqued the news reporting of his day, offering several “fake news” pieces called “hoaxes.” He claimed that “the only way to get a fact into a San Francisco journal was to smuggle it in.”

The Political Analyst: Amy Holmes fills the bill here. Called an “unconventional voice in political news, no one on the panel has a sharper sense of the happenings inside the beltway than Ms. Holmes. Previously a senior speechwriter for former Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, Ms. Holmes regularly appears on CNN’s prime-time line-up including Larry King Live, Anderson Cooper 360, Glenn Beck, and Headline News. No doubt, she will shed light on this Twain comment: “The political and commercial morals of the United States are not merely food for laughter, they are an entire banquet.”

The Scholar: Professor John Bird, Winthrop University, brings his vast knowledge of Mark Twain to play this part. Twain received several honorary doctorates, despite leaving formal education at 13. When Yale honored him with a Doctor of Literature, he exclaimed: “I was not competent to doctor anybody’s literature but my own, and couldn’t even keep my own in a healthy condition without my wife’s help.” Of course, Dr. Bird knows better. He is the original editor of The Mark Twain Annual, an honored teacher, and the recent author of Mark Twain and Metaphor.

When introduced in London as one of the world’s greatest authors Twain responded: “I was sorry to have my name mentioned in such company, because the World’s Greatest Authors have a sad habit of dying off. Chaucer is dead, Spenser is dead, so is Milton, so is Shakespeare, and I’m not feeling too well myself.” Well, he’s not quite dead yet—that report has been greatly exaggerated. His words in his voluminous writing continue to speak to us. Come hear how on April 24 when the trouble begins at 7.

One Trackback

[…] Twain articles written by Ben that have appeared on this website can be found here, here, and here. A description of a symposium he set up involving Peter Sagal of National Public Radio, […]