A couple of students have increased my appreciation for Shakespeare’s cross-dressing comedies. For years I’ve seen Twelfth Night and As You Like It as stealth opportunities for Shakespeare to escape the straitjacket of rigid gender expectations. In these two plays one sees men exploring their female side and women exploring their male side, men expressing their love for other men (but it’s socially okay because we know they are actually women) and women expressing their love for other women (but it’s socially okay because they think they are men). Through this comedy of gender confusion, Shakespeare is able to touch on taboo areas and then neatly extricate himself with happily-heterosexual-ever-after endings.

But students Elaina Straub and Helen Parshall have opened my eyes to new twists and turns. In my intro to lit class last semester, Elaina, a very fine student athlete, looked at Rosalind’s frustrations in As You Like It at having to deny the girl inside while maintaining a male façade. This is a 21st century interpretation I never anticipated. Helen, meanwhile, is using her senior project to explore what she calls “companionate marriage.”

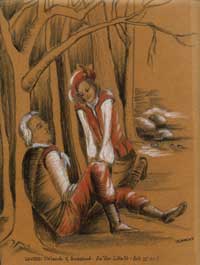

Elaina is a senior sociology major who took my class to fulfill our college’s arts requirement. She was primed to look at gender roles in Shakespeare’s comedy because her senior project involves exploring the gender make-up of different college disciplines. For her, then, Rosalind and Orlando in As You Like It are trying to break out of traditional roles (maybe like a female physics major), so that, in the Forest of Arden, Orlando gets to be more sensitive (he posts sentimental love poetry on all the trees) and Rosalind/Ganymede gets to be more assertive. So far the essay was going as I expected.

But then Elaina started focusing on Rosalind’s frustrations with having to maintain this strong male exterior. She quoted the giddy moment when Rosalind, still disguised as Ganymede, realizes that Orlando loves her:

Alas the day! What shall I do with my doublet and hose? What did he say when thou sawest him? What said he? How looked he? Wherein went he? What makes him here? Did he ask for me? Where remains he?…

It is now more acceptable for women to be assertive, but this has created new tensions. Elaina found herself liking the fact that Rosalind isn’t entirely de-feminized in the process. While she appreciated the strong Rosalind, she also liked the fact that Rosalind had the freedom to connect with her “inner girl.”

In other words, while some women find it liberating to see Shakespeare’s cross-dressing women acting like men, others like Elaina find it freeing when those women acting like men also have permission to behave like stereotypical women as well. Maybe it’s a case of third wave feminism meeting second wave. The fact that Elaina’s essay became a bit tangled at this point shows just how complicated gender roles have become, but the final upshot is that, as Elaina wrote, “In the forest, Rosalind is able to control her own life.” We should all be able to be who we want to be.

Shakespeare’s play gives us a chance to try out different selves in a safe environment with his play, like the Forest of Arden, functioning as a green world. Then the play ends and we reenter our own complicated relationships.

Helen in her senior project is taking a slightly different tack as she explores companionate marriages. Our department’s Shakespearean Beth Charlebois informs me that the coinage is not new and has been around for a while, but it’s new to me. More importantly, Helen is using it to explore what she wants in her own relationships.

I only talked to Helen briefly about her idea but here’s what I think she’s doing. In Shakespeare’s day, stereotypical gender expectations kept men from having the kind of friendships with their wives that they had with their male friends. Orsino, for instance, places Olivia upon a pedestal and Orlando sentimentalizes Rosalind to such a syrupy degree that the jester Touchstone satirizes his verses.

To suggest that a different kind of marriage is possible, Shakespeare has Viola and Rosalind dress up as men and develop strong male-like friendships with Orsino and Orlando respectively. Although they then transform back into women, we have been presented with a possibility that husbands and wives can now have close confidential relationships. Why go to the pub when you can share heartfelt confidences at home?

I assume Helen is looking at her subject from both gender angles. Olivia doesn’t want a man who worships her but rather one who talks straight, as Cesario does. And in a conversation that reminds me of those sex columns written by women for men’s magazines, Rosalind teaches Orlando how she would like to be courted.

Rosalind. Come, woo me, woo me; for now I am in a holiday humor,

and like enough to consent. What would you say to me now, an I were your very very Rosalind?

Orlando. I would kiss before I spoke.

Rosalind. Nay, you were better speak first; and when you were

gravell’d for lack of matter, you might take occasion to kiss.

Very good orators, when they are out, they will spit; and for lovers lacking—God warn us!— matter, the cleanliest shift is to

kiss.

Orlando. How if the kiss be denied?

Rosalind. Then she puts you to entreaty, and there begins new

matter.

Marriage counselors tell us that relationships work best if the couple clearly communicate their desires to each other. On the eve of their marriage, Orlando and Rosalind are already practicing this important skill.

Think of William Shakespeare as a couples counselor extraordinaire!