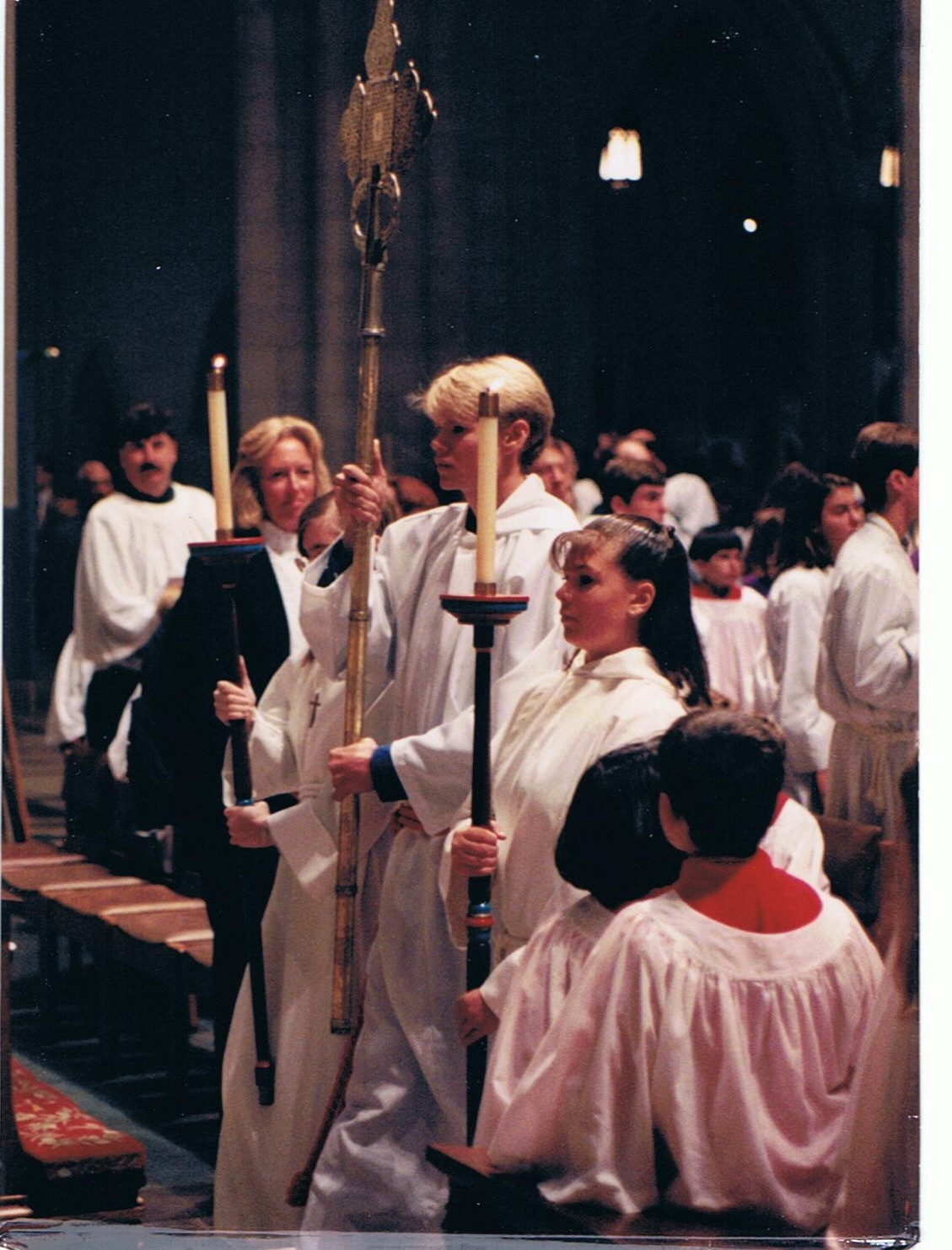

Justin at 16 carrying the cross at the National Cathedral

I am devoting this week to a work that came to my aid when I was dealing with the death of my oldest son nine years ago. I will introduce you to Justin and then describe how a medieval romance, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, helped give me images and a framework for the grieving process. I will also describe how the poem continues to help me as I support a very close friend who is dying of cancer. My ultimate goal in all of this is to explore the kind of help that literature can provide in our toughest times. Over the upcoming months and years, I will return regularly to this topic. But I give the upcoming entries to Justin and to this Camelot story.

Justin was the oldest of my three sons, each of whom I find to be a marvel. Justin was 6’3”, which astounded me since I am only 5’9” and we don’t have many tall people in our family. At the time he died, he had just turned 21. He was a religious studies major who wrote essays about St. Paul. He was very passionate about life and wanted to feel deeply. He was also one of the kindest people I have ever known. He loved children and had a wonderful way of entering their fantasy worlds.

Justin had a way of throwing himself into whatever he was doing. I remember him taking an African dance class and, when I watched his concluding performance, I was struck by how completely he gave himself over to the movement and the drumming. He was an athlete and would sacrifice his body to make plays. I remember him throwing himself at balls in the outfield, and one of his greatest moments was when he was on a 13-year-old all-star team and made a diving catch in centerfield. He would play basketball without fear of getting hurt, and sometimes his reckless abandon got him into trouble. He once twisted his knee badly on a dance floor (I think someone stumbled into him) because he wasn’t paying attention. He once broke his leg playing youth soccer.

These details I recall because they also help explain his death. But I need to talk about one more thing before I get to that. His junior year of college, Justin got caught up in evangelical Christianity. It was of a piece with the rest of him—he wanted to be absorbed in spirituality, just as he wanted to be absorbed into music and movement and everything else. He became associated with a church that got him to “declare Jesus Christ as my Lord and savior” and that made him feel that it was his mission in life to convert his family. His family, not surprisingly, experienced this as irritating (his younger brothers saw it as bullying), and we had a tense few months. (We finally made a rule that Justin couldn’t evangelize family members—“no man is a prophet in his home country,” Jesus would have said.) As his father, I just saw this as another stage in his growth and, while I refused to argue theology with him, I continued to love him and hug him. And he, after an intense half-a-year of conversion attempts, started to mellow. He no longer quoted scripture about leaving his mother and father, or about separating the sheep and the goats. (Justin was such a generous soul that, in the end, he couldn’t really imagine anyone going to hell—he just was trying out the idea that there could be boundaries.) One of the best things I ever did was give over an entire weekday afternoon to talk to him (at the time he was attending St. Mary’s where I teach—he was on leave from Grinnell College), even though it was the end of the semester and I had a two-foot stack of essays to grade. It was the last time I talked to him.

That’s because, the following Sunday, he threw himself into the St. Mary’s River (which runs by the college), got caught by a vicious current, and was swept out into deep water and drowned. I need to explain the “threw himself.” Justin had devised a kind of ritual—when he was feeling particularly joyous, he would sometimes go down to the waterfront and throw himself, fully clothed, into the water. I think he loved the sensual immersion of the action, and I think it had become a kind of cleansing rite as well. On the day that he did this, he was feeling more spiritually open than normal. It was April 30, 2000, the Sunday after Easter (which was late that year). He had traveled to Charlottesville, Virginia the night before and been inspired by a preacher there and had decided that he would be a missionary. (Knowing Justin, I don’t know that he would have settled on this—he was constantly changing his mind about such things.)

Justin had attended three church services the morning of his death (the Episcopal Church in which he had been brought up, along with two evangelical churches), which makes four services in the 24 hours before he died. Voltaire, who began to have doubts about God when hundreds of Lisbon churchgoers died in a Sunday earthquake, would have found this darkly ironic and worthy of philosophical and theological exploration, but I never have. The weather was stunningly beautiful, his friends reported him in high spirits, and at some point he went running down the hill to Church Point, a little spit of land with a cross that juts into the St. Mary’s River. According to a couple of students who saw him, he ran up to the cross calling out, “Jesus, Jesus” and kissed it. It seemed to be such a private moment that they left, and next thing anyone knew, he was in the water being carried by the currents.

Knowing Justin as I do, I can imagine that he threw himself in the water in a paroxysm of joy. What he didn’t know was that the currents were abnormally strong at the time. Spring of 2000 has seen a record-breaking amount of rain, even though April 30 itself was beautiful. In fact, it was one of the first beautiful days we had seen, which accounts even more for Justin’s euphoria. At any rate, it took the rescuers a while to find his body. We watched from the cemetery that overlooks the river as they searched for it.

The reason I go into such detail is because I feel that I must know why he was in the water. For 24 hours or so, I thought he was depressed and self-destructive. No one could figure out what he was doing in the St. Mary’s River, given how cold it was. We even wondered whether he had suffered from hypothermia, but the coroner informed me that he had not. It was only when I talked with all the students who had seen him that day that I realized he was not depressed. At a dark, dark time, this realization was one of the first glimmers of light I had. If the drowning was an accident, regardless of how thoughtless, that was far better than it being a self-destructive act. When I put all I knew together and when I later learned that he had thrown himself into the water on previous occasions, the narrative became less bleak. In fact, throwing himself into the river wasn’t particularly reckless. Church Point is a place where, during the summer, people will take their children to swim.

I found myself then thinking of all those times when teenagers seek out thrills and test limits, whether in a car or elsewhere. Most don’t die (although some do). There is a passage I recall (no doubt imperfectly) from Stephen King’s The Girl Who Loved Tom Gorton where an agnostic father figures there must be some supernatural force operating in the world that cares for people or a lot more teenagers would die during prom week. But these supernatural forces, if they exist, did not intervene in this case.

I like to imagine (perhaps this is wish fulfillment but I believe it be true) that, when Justin realized he was drowning, after first panicking and calling out for help (someone on the shore heard him calling out what was probably “Jesus”), he then surrendered and opened himself up to the next great adventure. I have no assurance that this in fact happened. My colleagues in the psychology department periodically point out to me that I often think I’m describing facts when in fact I am projecting. But this scenario I hold on to as a kind of bedrock truth.

I have never gotten over Justin’s death. Nor do I want to. When I have what I call “Justin moments,” attacks of sadness and depression, I treasure them because they remind me of how much I love him. But I haven’t let Justin’s death take over my life or poison my relations with my other sons or with my wife. In fact, we have all become closer.

I will no doubt have more to say about Justin in future entries. But as this website is devoted to exploring the role of literature in our lives, I will turn in the next entries to how I found solace in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in the weeks following the death.

3 Trackbacks

[…] written a number of times about the death of my oldest son Justin, in a drowning accident, at 21. You can read about the account here. Today I want to talk about how magical the number three seemed then, how difficult is has been to […]

[…] will conclude with my own experience with intense pain, although this pain was psychological. When my oldest son drowned and I was floundering in darkness, somewhere along the way I found myself thinking, “if this is a […]

[…] on life and death that I know. (A year and a half ago I wrote a series of posts, beginning with this one, on how it helped me cope with the death of my oldest son.) It is also, I believe, a wonderfully […]