Spiritual Sunday

Julia and I attended the final Harry Potter movie last week, and I was reminded again how Christian the story is. Given that for years certain evangelical Christians have been criticizing, banning and occasionally burning J.K. Rowling’s books, what are we to make of their inability to appreciate Harry’s Christ-like sacrifice as the end of The Deathly Hallows? And why, if they think that Rowling embraces Satanic magic, are they enthusiastic about C. S. Lewis’s Narnia Chronicles—which, after all, are also filled with witches, giants, satyrs, centaurs, etc.

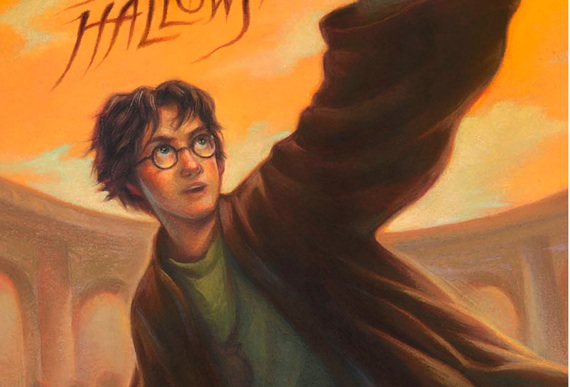

Let’s start off first with what I see as the book’s Christian message. At the end of The Deathly Hallows, Harry is faced with a terrible choice. Realizing that he has a piece of Voldemort’s soul within him—the soul that is helping keep Voldemort alive—he must allow himself to be killed by the dark Lord in order to defeat him. Seen in Jungian terms, Rowling is working out a doppelganger drama where Harry must rise above his own dark side if he is to achieve full self-actualization. In Christian terms, he must lose his life to find it.

Harry chooses to sacrifice himself because of his love for his friends. Just as Jesus descends to the dead, so does Harry, where he converses with father figure Dumbledore. What he sees there is a vision of Voldemort’s suffering, not of his power, and when he returns to confront the archvillain, he offers him the chance to express remorse. He is guided by compassion, not hate and fear. Voldemort may think that he has become master of the world’s most powerful weapon—the elder wand—and yet when he directs its force against Harry, it rebounds and kills him. Love has triumphed over death and the grave. Hallelujah.

Now think of the corresponding scene in Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, taught in many Christian schools and Sunday school classes. (See my post on this here.) The Christ-like Aslan sacrifices himself to redeem the sinner Edmund, who has betrayed his siblings, and he is essentially crucified by the White Witch on the stone table. But the witch doesn’t understand there is a deeper magic, just as Voldemort doesn’t realize how Harry’s mother, Snape, and Harry himself can be guided by love. She understands no more than Voldemort how Aslan is able to return and prevail.

Notice how, for me to pull religious meanings out of these two books, I must real episodes symbolically. I have written several times about the deadening tendency of certain rightwing evangelicals to interpret the Bible literally. Yet many are willing to engage in symbolic thinking when it comes to reading Lewis’s religious allegories. What gives?

First, this is not a new split. The tension goes back at least as far as the Protestant reformation (I don’t think Catholics have the same problem with symbolic thinking), and it shows up in one of the greatest literary examples of Christian allegory. John Bunyan’s defense of Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) gives us some insight into today’s confusion about Narnia and Harry Potter.

Bunyan was very nervous about publishing his account of Christian’s journey to the celestial city, a journey in which he is in constant danger of being waylaid by such obstacles as the Slough of Despond, Vanity Fair, and false friends like Obstinate and Pliable. Bunyan acknowledges that, when he showed his book to acquaintances, some attacked it. They accused him of engaging in lies, passing off the made-up as true.

As a preacher, however, Bunyan knew that fictional stories provide a powerful means to hook a congregation. (At one point in his introduction he even uses a fishing metaphor—one has to tickle one’s prey.) Bunyan knows that Pilgrim’s Progress is good preaching. He frames his defense in terms of an argument.

His critics, he says, claim that Pilgrim’s Progress is dark (by which he means confusing), feigned and insubstantial. When one is speaking of God (and that’s all that one should be speaking of), then one should use direct speech, not made-up frivolous stories. Here is a portion of the dialogue, beginning with Bunyan’s critics:

“Well, yet I am not fully satisfied,

That this your book will stand, when soundly tried.”

Why, what’s the matter? “It is dark.” What though?

“But it is feigned.” What of that? I trow?

Some men, by feigned words, as dark as mine,

Make truth to spangle and its rays to shine.

“But they want solidness.” Speak, man, thy mind.

“They drown the weak; metaphors make us blind.”

When Bunyan refers to men who, with “feigned words, as dark as mine,/Make truth to spangle and its ray to shine,” who is he referring to? Well, the big guns: Jesus, Paul,the disciples, the prophets, and the authors of the Bible. After all, they all used metaphors—and certainly not with the intent of making us blind:

The prophets used much by metaphors

To set forth truth; yea, who so considers Christ,

His apostles too, shall plainly see,

That truths to this day in such mantles be.

And

But yet grave Paul him nowhere did forbid

The use of parables; in which lay hid

That gold, those pearls, and precious stones that were

Worth digging for, and that with greatest care.

Bunyan concludes that it’s all right if he says one thing to mean something else. After all, when we dig into his parable, just as when we did into holy writ, we will find gold, pearls and precious stones:

I find that holy writ in many places

Hath semblance with this method, where the cases

Do call for one thing, to set forth another;

Use it I may, then, and yet nothing smother

Truth’s golden beams: nay, by this method may

Make it cast forth its rays as light as day.

And now before I do put up my pen,

I’ll shew the profit of my book, and then

Commit both thee and it unto that Hand

That pulls the strong down, and makes weak ones stand.

Bunyan may sound confident but he is very much on the defensive. The Puritans were strongly suspicious of fiction, a suspicion that they passed on to America through the Pilgrims. Fiction, after all, is not held in high regard in this country. Other cultures may honor storytellers highly but we have many parents who, when they see their kids burying themselves in the Harry Potter books, fear that they are being sidetracked from what is important.

If the Harry Potter series were seen and taught as Christian allegories, could they take on the respectability of Narnia? Do fans just have to make a case? The furor over the Rowling series does seem to have calmed down.

Bunyan’s detractors weren’t wrong to be worried, however. Once Bunyan noted that there is fiction in the Bible, he has opened up a can of worms. How deep does that fiction reach? Maybe God didn’t create the world in six days and maybe there was no Noah’s flood, no Tower of Babel. Maybe those are all allegories as well. I can see fundamentalists worrying about that, if we acknowledge some events to be allegorical, we created a crack in the dike.

I’ve written in the past that the issue is about control. Many Christian parents are afraid of their children slipping beyond their control and want to direct their schooling and their reading. If the kids do read Narnia, these parents want to make sure they are interpreting it correctly. If Harry Potter gains acceptance in this community, parents may try to similarly restrict interpretation.

Good luck with that. No matter how hard one tries, one can’t control entirely control a child’s imagination (although one can turn out repressed and guilt-ridden children). Books like Pilgrim’s Progress and Narnia and Harry Potter will make their way into the world, and into children’s hands, because they stem from a deep delight.

Bunyan describes how this delight overtook him when first he stumbled onto the idea for his book. He was writing something serious (about the saints) when suddenly fantasy took over:

When at the first I took my pen in hand

Thus for to write, I did not understand

That I at all should make a little book

In such a mode; nay, I had undertook

To make another; which, when almost done,

Before I was aware, I this begun.

And thus it was: I, writing of the way

And race of saints, in this our gospel day,

Fell suddenly into an allegory

About their journey, and the way to glory,

In more than twenty things which I set down.

This done, I twenty more had in my crown;

And they again began to multiply,

Like sparks that from the coals of fire do fly.

Puritan though he may be, Bunyan knows there is something right about the delight he takes in his story:

Thus, I set pen to paper with delight,

And quickly had my thoughts in black and white.

For, having now my method by the end,

Still as I pulled, it came; and so I penned

It down: until it came at last to be,

For length and breadth, the bigness which you see.

Fiction and the delight we take in it are from God. Amen.

Go here to subscribe to the weekly newsletter summarizing the week’s posts. Your e-mail address will be kept confidential.

One Trackback

[…] A John Bunyan Defense of Harry Potter This entry was posted in Rowling (J. K.) and tagged Harry Potter, International politics, J. K. Rowling, warfare. Bookmark the permalink. Post a comment or leave a trackback: Trackback URL. « Which Shakespearean Hero Is Murdoch? […]